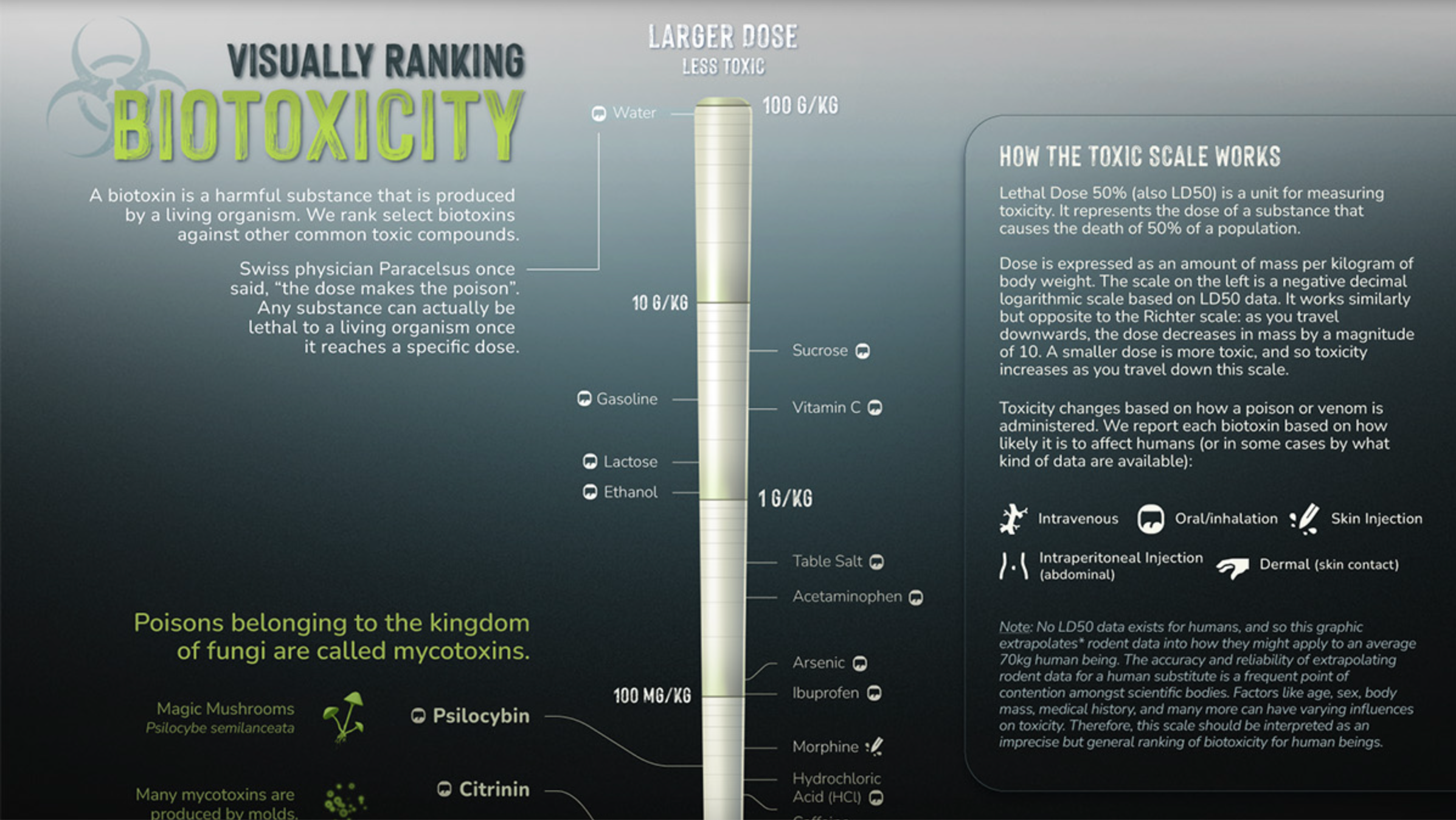

Biotoxins are harmful substances that come from living organisms. They can take many forms, from the venom of a snake or spider to the neurotoxins produced by certain types of algae or microbes. In the infographic above, we look at some common biotoxins in nature and rank them based on how deadly they are to an average 70 kg (154 lb) human being.

Ranking Biotoxins on a Toxic Scale

A basic concept in toxicology is that “only the dose makes the poison”. Everyday harmless substances like water have the potential to be lethal when consumed in large enough concentrations. Measuring a lethal dosage is very difficult.

First, living things are complex: factors like size, diet, biochemistry, and genetics vary across species. This makes it difficult to qualify toxicity in a universal way.

Second, individual factors like age or sex can also affect how deadly a substance is. This is why children have different doses for medications than adults.

Related: App in Tampa Works on Revolutionizing Healthcare Staffing Problems

Third, how a poison is taken into the body (orally, intravenously, dermally, etc.) can also impact its deadliness.

As a result, there are many ways to measure and rank toxicity, depending on what substance or organism is under investigation. Median lethal dose (LD50) is one common way for measuring toxicity. LD50 is the dose of a substance that kills 50% of a test population of animals. It is commonly reported as mass of substance per unit of body weight (mg/kg or g/kg). In the graphic above, we curate LD50 data of some select biotoxins found in nature and present them on a scale of logarithmic LD50 values.

What’s surprising is just how potent some toxins can be.

Bits and Bites about Biotoxins

While one would think that biotoxins are avoided at all costs by humans, the reality is more complicated. Here are some interesting facts about biotoxins present in nature, and our unusual relationships with the organisms that create them:

1. Fungi and molds make poisons called mycotoxins

Mycotoxins are a global problem. They affect crops from many countries, and can cause significant economic losses for farmers and food producers.

2. Phytotoxins can defend plants…and attack cancer

Plants use phytotoxins to defend themselves other organisms, like humans. Urushiol, for example, is the main toxic component in the leaves of poison ivy, poison oak, and sumac. But the Pacific yew tree produces taxol that’s valuable in chemotherapy treatments.

3. Fire salamander toxin is an ingredient in Slovenian whisky

Though not widely available, some whisky makers in Slovenia use samandarine from the fire salamander to create a psychedelic alcohol.

4. Ciguatoxins exist in the guts of reef fish

Very unique species of bacteria living in the digestive tract of reef fishes make ciguatoxin. They transmit this poison to other organisms when the host fish is eaten.

5. Pufferfish are deadly, but also delicious

Pufferfish contain tetrodotoxin, a potent neurotoxin in their ovaries, liver, and skin called tetrodotoxin. Despite being a delicacy in many countries around the world, it has a lot of strict regulations because of its ability to kill people. In Japan, for example, only specially licensed chefs can prepare pufferfish for consumption.

6. Batrachotoxin is lethal to the touch

The skin of some poison dart frogs secretes a deadly substance called batrachotoxin. It is so potent that simply touching the poison can be fatal. Indigenous people of Central and South America used batrachotoxin to poison the tips of hunting weapons for centuries.

7. Botox contains the most deadly biotoxin known

Commercial botox uses an extremely small amount of biotoxin from a microbe called Clostridium botulinum. It paralyzes the muscles, preventing contraction (i.e. wrinkling). It is the deadliest known biotoxin on Earth. One gram of botulinum toxin can kill up to one million people.

Caveats of Measuring and Reporting Biotoxicity

While we use LD50 data to rank biotoxicity, it isn’t an exact science. There is room for improvement.

For starters, no LD50 data exists for humans. That means data from other organisms has to be converted to apply to humans. There is a lot of contention amongst scientific communities about how accurate this is.

There has also been an increasing effort to move to new methods of measuring toxicity that are not harmful to animals. Several countries, including the UK, have taken steps to ban the oral LD50, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) abolished the requirement for the oral test in 2001.

Now, new ways of evaluating toxicity are under investigation, like cell-based screening methods.